NPS 3.0

Editor's Note: In 2003, Frederick Reichheld published an article titled "The One Number You Need To Grow" in Harvard Business Review, formally proposing the concept of Net Promoter Score (NPS). In the past 20 years, NPS has been widely used around the world, but at the same time, there have also been a lot of criticisms and doubts. Reichheld and his company Bain are constantly improving and iterating the NPS method. In November 2021, 18 years later, Reichheld once again published his latest article on NPS in Harvard Business Review - "Net Promoter 3.0: A better system for understanding the real value of happy customer". In order to solve the existing problems, he proposed a supplementary financial indicator - "earned growth rate".

Summary

Since its introduction in 2003, the Net Promoter System (NPS), which measures how well brands consistently convert customers into advocates, has become the mainstream framework for customer success today. But as NPS has grown in popularity, inappropriate use and even manipulation of NPS has begun to undermine its credibility. Unaudited, self-reported NPS undermined the usefulness of NPS. Over time, its creator, Reichheld, realized that the only way to solve this problem was to introduce a hard supplementary metric based on accounting results. In this article, he and two Bain colleagues introduce this metric: Earned Growth Rate, which reflects the revenue growth generated by repeat customers and their referrals. To calculate the Earned Growth Rate, companies must have a system to collect cost and revenue data for each customer and ask all new customers why they joined. If the reason is due to a referral, the new customer is an "earned" customer (Earned Customer); if it is due to advertising, promotions, or sales staff sales, the customer is a "bought" customer (Bought Customer). Earned growth rates reveal the true impact of customer loyalty because they are well-documented and auditable, helping companies validate investments in customer service and convince investors of the underlying strength of their businesses.

On a scale of 0 (not at all) to 10 (definitely), how likely are you to recommend our company to a friend? As a consumer, you’ve probably been asked this question many times—after an online purchase, at the end of a customer service interaction, or even after a hospital stay. If you work for one of the thousands of companies that ask customers this question, you’re familiar with the Net Promoter System (NPS), which Reichheld invented and first published in Harvard Business Review 20 years ago. (See “The One Number You Need to Grow,” December 2003.) Since then, NPS has spread rapidly around the world, becoming the mainstream framework for customer success—now used by two-thirds of Fortune 1000 companies. Why has it been so well received? Because it solves a major challenge that our financial system cannot solve: Finance can easily tell us when we’ve taken $1 million out of a customer’s wallet, but they can’t tell us when our work has improved a customer’s life. That’s the goal of NPS, which measures how consistently companies turn customers into advocates by tracking and analyzing three customer segments: Promoters, who are satisfied enough with their experience to recommend your brand to others; Passives, who feel they got what they paid for but nothing more and are not loyal assets with ongoing value; and Detractors, who are disappointed with their experience and are hurting your company’s growth and reputation. Promoters are those who rate 9 or 10, Passives are those who rate 7 or 8, and Detractors are 6 or lower. To calculate your company’s overall Net Promoter Score, subtract the percentage of customers who are Detractors from the percentage of Promoters. While the algorithm may seem simple, the entire system is designed to incentivize teams to deliver experiences that are not just satisfying, but exceptional. When customers feel cared for, they come back for more and bring their friends. The power of customer referrals is also demonstrated by the extraordinary success of NPS leaders, highlighted in Reichheld’s latest book, The Ultimate Question 2.0, featuring 11 public companies. Over the past decade, their median total shareholder return has been five times higher than the median U.S. company (based on public companies with revenues of more than $500 million as of 2010). These results have prompted more companies to monitor their Net Promoter Scores—and some to report their NPS metrics to investors. Unfortunately, self-reporting and misinterpretations of the NPS framework have begun to sow confusion and undermine NPS’s credibility. Inexperienced practitioners have abused it by tying the Net Promoter Score to bonuses for frontline employees, who care more about their NPS scores than about learning how to better serve customers. Many companies have amplified the problem by publicly reporting their scores to investors, without adequately explaining the process by which they arrived at the scores, and without taking effective steps to prevent soliciting high scores from customers (“If you don’t give me a 10, I’ll lose my job”), even bribing customers (“We’ll give you 10 free oil changes”), and manipulating NPS surveys (“We never send surveys to customers whose claims were bounced”). Nor is there information provided about which customers (and how many) were surveyed, what their response rates were, and whether surveys were triggered by specific transactions. Reports rarely mention whether the study was conducted by credible third-party experts using double-blind methodology. In other words, some companies have turned Net Promoter Score into a vanity statistic that undermines the credibility of NPS. Over time, we realized that the only way to make the system work better was to develop a complementary metric that leverages accounting results rather than surveys. We needed a metric that could illustrate the quality of a company’s growth (and potentially profitability) based on audited revenue from all customers, not just a potentially biased sample of survey responses, to better protect against manipulation, solicitation, solicitation, and sample response bias that can contaminate the results of non-anonymous surveys. We can safely say that we have successfully developed such a metric. Unfortunately, self-reported scoring and misunderstanding of the NPS framework have created confusion and reduced the credibility of NPS. In this article, we introduce “earned growth” as a counterpart to NPS based on accounting results, which will strengthen the validity of NPS and provide companies with clear, data-driven connections between customer success, repeat and incremental purchases, word-of-mouth recommendations, positive corporate culture, and business results.

Sources of Earned Growth

The economic advantages of companies with high Net Promoter Scores prove that generating more promoters (assets) and fewer detractors (liabilities) drives sustainable growth. But we knew we needed to reinforce NPS in a more objective way. Even with enhanced digital information and big data monitoring, the scores generated by questionnaires are inherently soft, and company management (and investors) need a hard metric that someone can be held accountable for. Reichheld found the inspiration for "earned growth" while studying the slide deck that an investor prepared for a keynote speech by First Republic Bank management. The bank had quantified how much of its growth came from repeat customers—and also from bringing their friends. Existing customers accounted for 50% of deposit balance growth, and referrals accounted for 32%, according to the slide deck. That means 82% of the bank's deposit growth came from providing a great customer experience. On the loan side, 88% of growth came from keeping existing customers happy. The bank has data on referrals because it asks each new customer the main reason they chose the bank and records the answer in the customer profile. The bank's customer accounting system automatically combines households with related small businesses, so the bank can also easily see how much deposit and loan balances of existing customers have grown. The main reason First Republic Bank collected this data was to prove to investors (and regulators) that its rapid growth was safe and high-quality. In an industry that typically grows 2% to 3% per year, the bank's loans were growing 15% per year. In many cases, this would raise red regulatory flags, as it could indicate that the bank was lowering credit standards to gain market share. But the data shows that it was growing without increasing risk. Image: Manuela & Stefan Kulpa

Manuela and Stefan Kulpa are a husband-and-wife team fascinated by the unique personalities of the animals they photograph, and the intrinsic connection that exists between people and animals. The slide presentation inspired Reichheld to develop a new metric, "earned growth rate," which measures the growth in revenue generated by repeat customers and their referrals. A related statistic, earned revenue share, is the ratio of earned growth to total growth. This is what First Republic Bank shows in its slide—82% for deposits and 88% for loans. Since the bank's total loans are growing 15% per year, its loan earned growth rate is 13.2%. We estimate that few other banks can match First Republic Bank’s earned growth performance, but we can’t really know until more banks start measuring and reporting their earned growth statistics. But we do know that First Republic Bank’s percentage of new customers generated through referrals (71%) far exceeds that of its retail banking peers (as measured by Bain’s NPS Prism study), which ranges from 21% to 53%. In a very different industry, DTC prescription eyewear pioneer Warby Parker acquires nearly 90% of its new customers through referrals. Warby was one of the first companies we tested the earned growth framework with, and the metric helped us see Warby’s impressive loyalty-based growth. The company is a longtime NPS practitioner and plans to continue using Net Promoter Score as a key metric for internal management, but it also plans to strengthen its learning capabilities through earned growth.

Calculating Earned Growth

While it’s possible to estimate earned growth without access to a company’s internal data, investors demand accurate (and audited) statistics based on actual results. To capture the hard data they need, companies must upgrade their systems to include customer-based financial data. A basic customer accounting system tracks each customer’s costs and revenues over time, churn patterns, spending reductions, and price discounts, as well as segmented customer tags during that time. It also collects the reasons each customer joined (e.g., whether the customer was “won” through referral or word of mouth, or “bought” through advertising, promotions, or sales), as well as the cost of acquiring that customer. Essentially, this is also the core information needed to estimate customer lifetime value (CLV). However, CLV is much more complex, involving probability and advanced mathematics (think actuarial science). While it can yield powerful insights, its application relies on complex expertise. While CLV involves predictions about the value a business can earn from customers, earned growth looks at actual results and quantifies the actual value earned. Earned growth helps each team understand how it’s performing—by tracking growth from repeat customers, and growth from friends they refer. There are two elements to earned growth. The first component is called Net Revenue Retention (NRR), a metric that measures the portion of growth that comes from repeat customers, and it’s been used in multiple industries, most notably the Software as a Service (SaaS) industry. Once you’ve broken down your revenue by customer type, you can determine your business’s NRR. Simply calculate the revenue generated by last year’s customers this year, divide it by your total revenue last year, and then express that number as a percentage. We added a relatively painless step to our onboarding process: Ask them why they decided to give their business to this company. The second component is Earned New Customer (ENC). This is the percentage of total revenue that was spent by new customers acquired through referrals (rather than through promotional channels). This data requires a little more work because companies must determine why new customers joined. We’ve developed a practical solution for this challenge, and while it may still require some experimentation and refinement, ENC is important to monitor. The sooner a business can get a reasonable estimate of ENC revenue, the better it can focus its investments in customer acquisition—and justify investing more in delighting existing customers. Today’s businesses often underestimate the role of referrals, viewing them as something nice to have rather than a necessary (and perhaps the most important) component of sustainable growth. To determine earned revenue growth rate, start by calculating NRR—because it’s typically the larger of the two components. To understand the importance of this statistic, consider how sensitive SaaS company valuations are to small changes in their NRR. Companies with NRRs above 130% are valued at more than 2.5 times that of companies with NRRs below 110%. Despite its importance, even experienced SaaS companies struggle to report NRR with great consistency. Some use a sample frame of customers, others exclude new customers that defected during the period, or customers who signed multi-year contracts, and so on. We strongly recommend that regulators make this a formal GAAP measure and develop precise reporting rules. In some industries, quantifying NRR may require a bit of homework. For example, not all brands aggregate accounts across multiple product lines or services, and accounting rules for customers that join and defect in the same period must be consistent. B2B companies will need to develop rules to clarify whether different divisions (or purchasing units) of the same company represent one or more customers. But with today’s sophisticated CRM technology, big data tools, and a little analyst hassle, it’s all doable, and it requires less work than arcane accounting measures like goodwill and depreciation—which, while required by GAAP, provide far less useful information.

We realized that the only way to make the system work better was to develop a complementary metric that leverages accounting results.

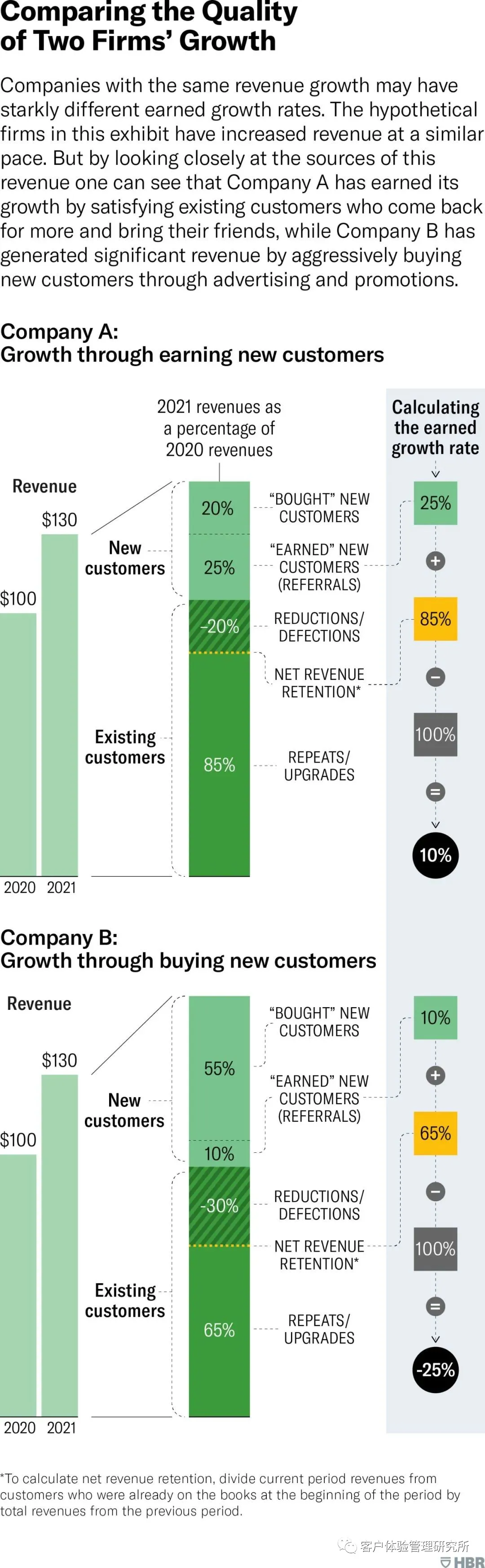

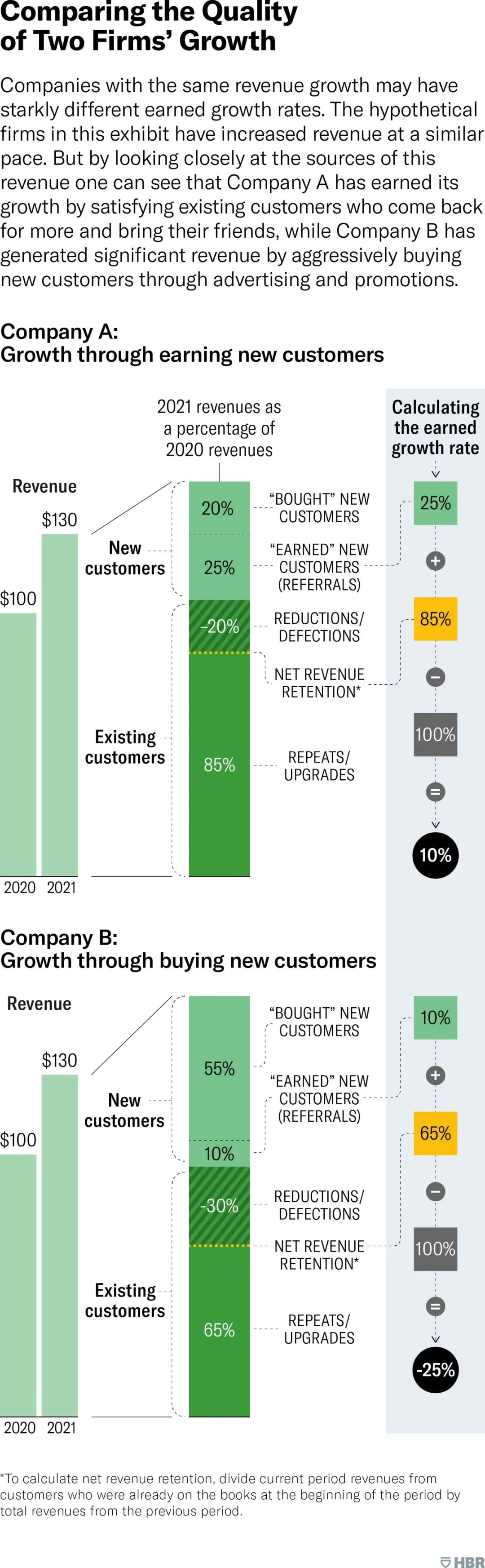

Now, let’s consider how best to approach the second component of earned growth: the portion of revenue that comes from earned new customers. Few companies can quantify this today, so we pioneered a solution that has proven effective in several ongoing beta tests. We added a relatively painless step to our new customer acquisition process: Ask them the primary reason they decided to give their business to this company. Do this at the beginning of the relationship, making sure the customer is clear about the decision and the reasons for it. The reasons given are then categorized into “earned” versus “acquired” categories. For example, if a customer selects “trusted reputation” or “recommendation from friends or family,” that customer and the associated revenue count as earned. Customers who select “helpful salesperson,” “advertising,” or “special or promotional pricing” are labeled as acquired. Our goal is to develop a universally applicable process so that every company can use the same methodology, resulting in comparable reporting numbers. But for now, a good solution is to pick a few reasons you expect customers to choose, plus an open-ended “other” option that collects data that can help companies adjust or add categories over time. Tracking the behavior of customers labeled earned vs. acquired will help determine their relative lifetime value, clarifying which customer segments and acquisition channels represent the best investments. In our consulting work, we have found that most companies find earned new customers more profitable than acquired customers, and many acquired customers are found to be unprofitable to the business over their lifetime. This customer-based accounting data is essential to implementing customer strategies, such as the one developed by our Bain & Company colleague Rob Markey. (See “Are You Underestimating Your Customers?” Harvard Business Review, January-February 2020). Treating customers as your company’s most important asset is just talk until you track and quantify the value of each customer. To determine earned growth rate, add NRR and ENC, then subtract 100%. Let’s look at a hypothetical example – Company A’s revenue grew from $100 in 2020 to $130 in 2021, or 30%. Of the 2021 customers, the revenue from customers on the books in 2020 was $85. Some of them increased purchases by a total of $5, but this increase was offset by other customers decreasing purchases by a total of $20, resulting in an NRR of 85%. New customer revenue was $45, of which $25 came from earned new customers (referrals) and $20 from acquired new customers. Adding NRR (85%) and ENC (25%), then subtracting 100%, gives an earned growth rate of 10%. Next, consider another hypothetical company that reports the same revenue growth as Company A, but with very different sources of growth. Company B’s NRR is only 65%, much lower than Company A’s. Although the two companies appear to be on the same track, Company B is achieving revenue growth by actively acquiring new customers. This will almost certainly hurt current and future earnings and prove to be an unsustainable strategy, but current GAAP accounting rules obscure this important difference.

Figure: Winning Growth Rate Comparison of Two Companies

Savvy investors and executives have not forgotten the real-world business impact of customer loyalty, and by developing auditable statistics, brands will be able to verify whether significant investments in providing excellent customer service are worthwhile. Now let's look at two real-world company cases, FirstService and BILT, which have begun using winning growth rate as a measure of customer loyalty.

Long-term economic value of recommendations

ay Hennick founded pool cleaning company FirstService when he was a teenager, and fifty years later, FirstService has annual revenues of more than $3 billion and 24,000 employees. It is the largest residential community management agency in North America, with a portfolio of property services businesses, including CertaPro Painters, California Closets, Century Fire Protection, and First Onsite. FirstService began implementing NPS across all of its businesses in 2008. When Reichheld met with current CEO Scott Patterson in 2011, Patterson explained that he was very interested in learning how NPS could help his business leaders build stronger relationships with their customers. The more we learned about the company, the more interested we became (Reichheld eventually joined its board of directors), primarily because it seemed to care about customer loyalty as much as we did. When Patterson heard about Reichheld's plans to develop earned growth, he responded, "That's a great idea, and it perfectly reflects the way we think at FirstService." FirstService attributes much of its success to a customer-centric culture, where business leaders in all regions understand that it takes a lot of spending to replace lost customers. They also know that it’s far more efficient to win new customers through word of mouth from existing customers. Patterson estimates that more than half of all new customers in its residential business (i.e., residential community management) come from referrals. In its California closet division, 70% of leads also come from referrals; in the paint business unit, CertaPro’s figure is 80% to 90%. Local franchisees know that word-of-mouth leads are more likely to result in good business (more than 90% for CertaPro—about twice as many as other leads). And because franchisees stay in close contact with their customers, they can learn who referred them and ask the referrer what made him or her the referrer. FirstService offers a compelling example of how investors can win customer loyalty. The company went public on the Nasdaq exchange in early 1995. At the time, the Bain team looked at all U.S. public companies with at least $100 million in revenue that year (about 2,800 companies) and ranked them based on total shareholder returns as of the end of 2019. FirstService ranked eighth (ahead of superstars like Apple), with an annual total shareholder return of nearly 22%. A $100,000 investment in FirstService stock in 1995 grew to $13.6 million by 2019. By tracking and publishing auditable earned growth rates, companies like FirstService can credibly demonstrate the source of their advantage, helping investors understand their sustainable loyalty growth.

Photo: Manuela & Stefan Kulpa

Patterson admits that he had a hard time convincing investors of the sustainable advantage of FirstService's customer-centric culture. "They heard my words," he says, "but their financial minds couldn't understand them, and they kept asking about the real secret behind our impressive performance so they could evaluate our future." He sees developing a measurable science around earned growth as an advantage. He's not worried about giving away the secret sauce—after all, a service-based culture is hard to build and maintain.

BILT's Winning Growth Exploration Report

In 2016, BILT launched a mobile app that replaces paper instructions with step-by-step 3D instructions for products that require assembly, installation, configuration, repair or maintenance. Manufacturers and retailers send computer-aided design files to BILT, which converts them into digital animations with voice commands and text prompts. Amazon, Ikea and Wayfair have acknowledged that poor assembly processes can negatively impact the customer experience, and they have tested new ways to simplify home assembly. In 2017, Ikea acquired TaskRabbit, an online marketplace that now connects more than 100,000 assembly service providers to make it easier for its customers to hire a handyman during the checkout process. Wayfair has partnered with Handy.com to offer a similar service. Earlier this year, Amazon began experimenting with a premium service that automatically includes assembly services at the time of delivery. BILT can help retailers significantly reduce the extra costs associated with assembly and customer support, and provide buyers with the knowledge and guidance they need to assemble items themselves. BILT even tracks how much time people spend on each instruction screen, which helps manufacturers and retailers identify confusing or unintuitive steps in the assembly process so they can modify and improve the experience. The app also gives consumers a virtual file cabinet for all product registration, warranty information, instructions, and troubleshooting tips. Instructions saved in the file cabinet are updated in real time, so they never become outdated. In other words, BILT can help retailers and brands improve the customer experience even after the product is assembled. At the end of the assembly process, the BILT app generates a classic NPS survey, asking consumers how likely they are to recommend the product on a scale of 0 to 10, with an open-ended question about the reason for the score, and suggestions on how to improve the experience. As a result, the app can provide retailers with rich customer feedback related to specific SKUs and customer purchase histories. On its website, BILT claims that its company's mission is to create "an experience so empowering that it turns consumers into promoters of the brands we serve." It's fascinating to see the emergence of a business that is entirely dedicated to helping other companies improve their NPS results. When Reichheld first encountered BILT in early 2020, its revenue was growing by more than 175% per year. As happens with most startups, business expansion consumes a lot of cash flow. But BILT was able to achieve an NRR of 150%, and most of its new customers came through referrals, resulting in an earned growth rate of 160%. This evidence convinced Reichheld that the company's growth was sustainable. He has since invested significantly in BILT and joined its board of directors.

Prosperity through helping others

When Reichheld began writing about loyalty in Harvard Business Review more than three decades ago, we had no idea how profound an impact we would have on the customer-centric movement (in "Zero Defects: Service Quality," September-October 1990). We are proud of what we have helped companies achieve, but we realize there is still a long way to go. Early on, we saw that customer loyalty had little to do with marketing gimmicks and flashy advertising, and later we demonstrated that it could generate significant economic advantages, including efficient customer acquisition. Today, we can be sure that business success begins when leaders embrace a fundamental proposition: that their company's primary purpose is to treat its customers with love. This approach generates loyalty, which drives sustainable, profitable growth. It underpins the financial prosperity of great organizations and helps make them great places to work. But its impact is notoriously difficult to quantify. It's time to get serious about measuring (and reporting) progress toward that goal, and recognizing that improving the lives of the people we serve is the only way to win.